(aka Pacing With Heart Rate Monitoring)

People who live with fatigue and less energy can live a better life through pacing strategies. This is essentially a way of eking out your available energy throughout the day by planning, slowing things down and choosing which activities can be done. You may have also heard about heart rate monitoring for Long Covid.

Heart rate monitoring is a subset of pacing. It works on the basic idea that a higher heart rate equals more energy used. Beyond that, it aims to prevent fatigue, pain and other symptoms by reducing the time spent above the anaerobic threshold. This concept is based on the research of the Workwell Foundation in the US and has been adopted as a pacing strategy by many people with ME/CFS. It may be a good option for people with Long Covid.

The Anaerobic Threshold

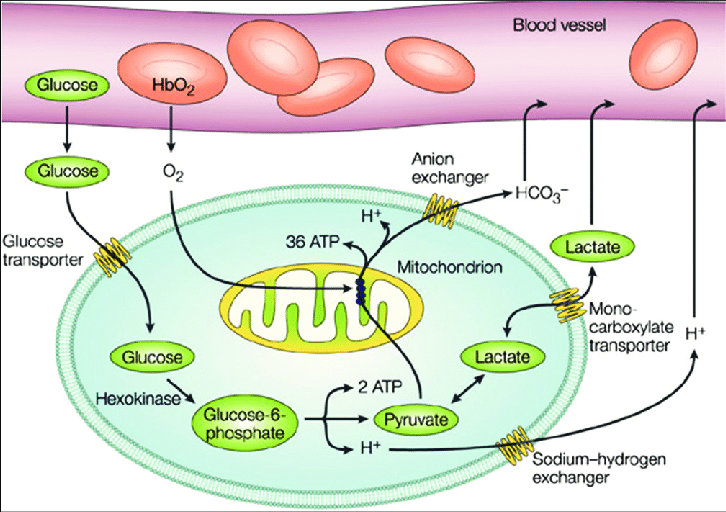

To begin, a bit of cellular anatomy knowledge is required. The cells in our body require energy in the form of a molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP). They obtain this energy from food (glucose) via the mitochondria, the “powerhouse of the cell”. The best way to produce ATP is with oxygen (O2). If no oxygen is available, the cell can use an anaerobic (”without oxygen”) process. This is less efficient and produces less ATP, which means less energy for the cell to operate well. Anaerobic processes also mean lactic acid builds up in the blood.

Advertisement

The Geek’s Guide To Long Covid is available as an ebook!

You’ll find a comprehensive guide to using wearables, apps and technology to cope with Long Covid. It offers detailed instructions on pacing, heart rate monitoring, HRV, POTS, deep breathing, tVNS, air purifiers, CO2 monitors and lots more.

Available from Amazon

In fitness terms, the “anaerobic threshold” is the point during exercise at which oxygen is no longer readily available and, under stress, the cells switch to an anaerobic process, causing a buildup of lactic acid. You may have seen that some fitness regimes distinguish between aerobic (or cardio) exercise and anaerobic exercise.

Aerobic exercise includes running, swimming, walking, cycling, elliptical exercises, team sports and other activities that use large muscle groups over a long period of time. It’s good for your heart, lungs and overall fitness.

Anaerobic exercise includes things like heavy weight lifting, high intensity interval training workouts and sprinting. These activities involve intense effort in short bursts. It feels more difficult to do, may make you gasp for air and can produce a burning feeling in the muscles. This type of exercise is said to help build muscles, burn fat and strengthen bones.

Fitness regimes aim to increase your anaerobic threshold through regular exercise by pushing the body into the anaerobic zones. In practice, it means you are better able to cope with intense exercise the more you train.

Everyone’s aerobic threshold is different and it depends on your sex, age and overall fitness. The number can be determined officially using exercise stress tests and equipment but most people estimate the figure using this formula:

First, calculate your maximum heart rate = 206.9 – (0.62 x your age).

The anaerobic threshold is said to kick in at around 80-85% of your maximum heart rate. The threshold at which lactate begins accumulating is 85% of maximum heart rate or 75% of maximum oxygen intake.

So the anaerobic threshold for a healthy person is [206.9 – (0.62 x your age)] x 0.85.

There are a lot of online heart zone calculators that will do this job for you. Here’s one.

It’s Different In People With ME/CFS (and maybe Long Covid)

In theory, people with ME/CFS (and maybe those with Long Covid) reach their anaerobic threshold at a lower heart rate than healthy people. The idea is that the mitochondria are malfunctioning or they’re not getting enough oxygen. It’s possible a metabolic switch has been flipped and the cells are more likely to resort to anaerobic processes to create ATP. This results in less overall energy and fatigue, along with more lactic acid buildup in the blood and muscle and subsequent pain. Too much time spent above the anaerobic threshold results in post exertional malaise (PEM) So ultimately the aim is to keep the heart rate at a level below which AT occurs and PEM kicks in.

It’s been suggested that people with ME/CFS keep their heart rate at only 50-60% of the maximum.

[206.9 – (0.62 x your age)] x 0.60.

The Workwell Foundation, a charity that researches ME/CFS, conducts two-day exercise tests to determine the threshold for people with ME/CFS. Without a test, Workwell suggests confining the maximum heart rate to only 15 beats per minute above resting heart rate. They suggest avoiding spending more than two minutes above that threshold.

Ultimately, finding your own threshold to prevent fatigue or PEM is a process of trial and error. Keeping a diary/record of what works and what doesn’t can be very useful.

How To Pace With Heart Rate Monitoring

If you decide to try this method of pacing, you’ll need to invest in some wearables and apps that give real-time heart rate information and an alarm for when your heart exceeds the threshold.

Calculate your maximum heart rate, your resting heart rate and the percentage or bpm at which you wish to avoid exceeding. To give an example, if your resting heart rate is 60bpm, you might want to avoid doing anything that makes your heart rate go over 95bpm. The actual rates vary according to each person.

Keep an eye on your heart rate and set an alarm to alert you if you have exceeded your maximum desired heart rate.

When going about your daily activities, take it easy. Be prepared to sit or lie down whenever your heart rate goes over the threshold. Adjust activities so you can sit or lie down while doing them. Apportion extra time for activities to account for pauses to rest and get your heart rate back down. Stop doing anything that causes your heart rate to go above the threshold for any sustained amount of time.

Be aware that pacing with heart rate monitoring can be a frustrating process, especially if you are being very strict and sticking to the 15bpm limit. It also will reduce your physical fitness. Not all doctors support this method of pacing. Those who advocate for pacing this way say it has been helpful in reducing the number of PEM / crashes and many people’s illness has slowly receded.

If nothing, else, keeping your heart rate low will lower the amount of energy you use each day and it may help with orthostatic intolerance and shortness of breath

Instructions For Wearables And Apps

Polar H10 Chest Strap and Heart Graph App

The Polar H10 is a wearable chest strap with a detachable monitoring device. It’s worn around the torso, just under the breasts/pecs. It detects your heart rate through electrical activity.

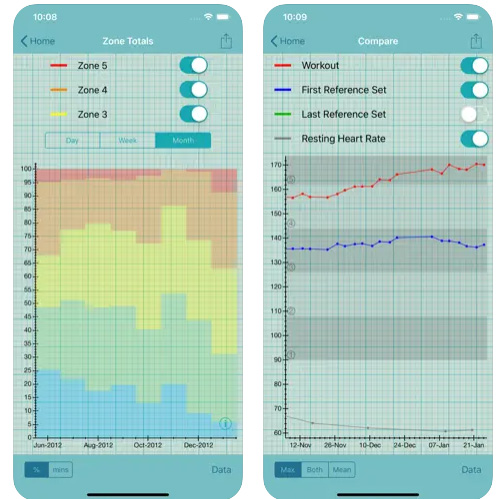

Heart Graph is an app that pairs with external devices like the Polar H10 or Apple Watch and accurately measures heart rate, providing a variety of graphs as well an alarm function.

The Polar H10 is a wearable chest strap with a detachable monitoring device. It’s worn around the torso, just under the breasts/pecs. It detects your heart rate through electrical activity.

Heart Graph is an app that pairs with external devices like the Polar H10 or Apple Watch and accurately measures heart rate, providing a variety of graphs as well an alarm function.

Combining the two is considered the “gold standard” of amateur heart rate monitoring because it is the most accurate reflection of heart rate and has a fast-acting alarm. The Polar is battery powered and thus doesn’t need recharging. Wear your chest strap all day (and even at night if you can tolerate it). Keep your phone handy at all times.

1. First, pair your Polar H10 with the Heart Graph app:

Go to Settings on Heart Graph > Scroll down to Paired Sensors > Search For Sensors > Select the Polar device that comes up.

2. Next, set the heart rate alarm:

Go to Settings on Heart Graph > Audio > Heart Rate Alarm > Maximum rate alarm > Set at your required bpm e.g. 95bpm. Alarm type is continuous alert.

3. You can also set the alarm to tell you what your heart rate is once it goes over your set threshold:

Go to Settings on Heart Graph > Audio > Spoken Heart Rate > Heart rate alarm > Toggle to “on”

4. Next, configure Heart Graph to show your heart rate zones:

Go to Settings on Heart Graph > Analysis and Display > Heart rate zones > Toggle to “on”.

Then under that you’ll find “Configure Heart rate zones” > Add in your desired 5 heart rate zones where “Maximal” is above your calculated anaerobic threshold.

Example:

Zone 1: Easy = 60bpm

Zone 2: Moderate = 75

Zone 3: Hard = 85

Zone 4: Very Hard = 95

Zone 5: Maximal = 105

If you want your alarm and graphs to be absolutely accurate, turn off Graph Data Smoothing.

You can also adjust the time length that the display shows:

Go to Settings on Heart Graph > Analysis and Display > Display Window > 90 Minutes

Note: Heart Graph can be paired with a variety of bluetooth chest straps. It will also pair with the Apple Watch. Be aware that the Apple Watch only provides the heart rate data, it doesn’t create the alarm. Word is that the Apple Watch will have heart rate zone alerts available after October 2022

Garmin Watches

At time of writing the best Garmin watches for heart rate monitoring are the Vivoactive 4 and the Venu range. Read more about Garmin devices on the Wearables page.

1. Set Your Heart Rate Zones:

Garmin has a a general setting where you can tell the wearable what your maximum heart rate is and it will then colour-code your heart rate graphs according to whether your daily activity went over your maximum HR threshold (e.g. If you’ve had a busy or bad day, there’ll be a lot of red). It can tell you how many minutes you spend over the maximum threshhold during an activity.

Instructions: Click the bottom button on the watch. Go to Settings (gear icon) > User Profile > Heart Rate Zones > Default.

Set your max HR e.g 100bpm.

Then: Set zone 5 at 90-100%, zone 4 at 80-90%, zone 3 at 70-80%, zone 2 at 60-70%, zone 1 at 50-60%. This will give you the colour-coded heart rate graphs

2. Set Up Your Heart Rate Alarm

You can also set some Garmin wearables to give an alarm if your heart rate exceeds a threshold. This is useful for pacing as it lets you know you’re doing too much and should rest or pace an activity. Be aware the alarm has a slight delay so if you are strictly pacing it’s not ideal. This alarm will only work if you are running an activity at the time. The yoga activity is the best option here and lets you see stress levels. Unfortunately Garmin updated their software a few months ago and you now can’t see real-time stats in the Connect app until your activity is finished and uploaded. Running an activity all day uses up the battery much quicker so you’ll need to factor in recharging time.

Instructions: Click the top button on the watch > Select Yoga as your activity > Swipe the screen up > Select Settings > Alerts > Heart Rate > High Alert > Custom > Enter your maximum desired heart rate e.g. 90 bpm

If you want the activity to show your heart rate as part of its data screen, follow the official instructions here.

Instructions: Click the top button on the watch > Select Yoga as your activity> Swipe the screen up > Select Settings > Data Screens > Heart Rate Zone Gauge. You can also select what other things the activity screen tells you while it’s on e.g. time, respiration rate, temperature etc

Fitbit Versa 2/3

Fitbit watches don’t automatically include a heart rate alarm but you can add the feature thanks to a couple of free apps. You’ll need to add the apps via your phone.

Instructions: Open Fitbit app > Open Account (top left hand corner profile pic) > Select your device (Fitbit Versa 2 or 3) > Apps > Search

- Search for these apps:

HRPacing by allyann (Recommended). This app, created by someone with ME/CFS, has a built-in anaerobic threshold calculator and will sound an alarm when you’re over that number. Or you can just use a straight up set bpm number for the alarm. The alarm will only sound a couple of times every 30 seconds. The app will show your heart rate, time, date and threshold number on the screen while active.

AlertMe by Karthik Subbarao. This app will create a heart alarm for your Versa. The alarm will vibrate continuously over a set bpm until you tap it or until your HR slows down. Unfortunately the app takes over the clock face and doesn’t have a lot of other info on it so you may choose to use this app only on occasion.

Stats and MedID by Jason Olsen. This app and clock face is designed more as a medical alert and emergency identification option but has a built in alert. It only buzzes once, though and you’ll need to tell it you’re OK. Otherwise it thinks you’re dying and will change the clock face to your emergency contact details.

2. Install one (or all) of those apps.

Once you’ve found the app, hit install.

Note: You’ll find the MedID clock face under “Clocks” not “Apps”

Once you’ve got the apps installed you’ll need to set up permissions and settings.

For HRPacing

Instructions: Open app > Permissions > Select all / toggle all to “on”.

Then: Settings > Alert by custom heart rate > Toggle to “on”. Then set your preferred custom heart rate e.g. 95bpm

OR: Settings > Anaerobic threshold tolerance > Set it to your desired figure. It’s automatically set at 0.6 which is equivalent to 60% of max heart rate, the recommended zone for people with ME/CFS

For AlertMe:

Instructions: Open app > Permissions > Select all / toggle all to “on” (give it access to your heart rate data)

Then: Adjust the settings on your watch (not in the app). Add in your desired maximum heart rate which will trigger the alarm

For Stats and MedID

Instructions: Open app > Permissions > Select all / toggle all to “on”

Then: Settings > Alert me if my heart rate goes above > Add in your desired maximum heart rate which will trigger the alarm

References

Keller, B.A., Pryor, J.L. & Giloteaux, L. Inability of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients to reproduce VO2peak indicates functional impairment . J Transl Med 12, 104 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-12-104

J. Mark Vanness, Christopher R. Snell & Staci R. Stevens (2007) (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J092v14n02_07, Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 14:2, 77-85, DOI: 10.1300/J092v14n02_07

Todd E. Davenport, Staci R. Stevens, Mark J. VanNess, Christopher R. Snell, Tamara Little, Conceptual Model for Physical Therapist Management of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, Physical Therapy, Volume 90, Issue 4, 1 April 2010, Pages 602–614, https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20090047

See Also

Angela Flack’s website Holistic Myalgic Encaphalomyelitis and her extensive listing of research into heart rate monitoring here