Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Tracking has become an important metric used by various wearables and apps. HRV can be used to ascertain how well your body is reacting to stress. In the realm of fitness coaching this can help with decisions about how hard to train on a particular day. When it comes to observing your own health, HRV can also be an indicator of general wellbeing and the ongoing state of your autonomic nervous system.

In terms of Long Covid, it has been proposed that some people with LC have dysautonomia and impaired vagal tone, with dysfunctional HRV results, typically lower HRV scores and more sympathetic swings. Thus, getting to know your HRV scores can be useful. HRV can help with pacing and with giving an overall picture of improvement or decline.

Advertisement

The Geek’s Guide To Long Covid is available as an ebook!

You’ll find a comprehensive guide to using wearables, apps and technology to cope with Long Covid. It offers detailed instructions on pacing, heart rate monitoring, HRV, POTS, deep breathing, tVNS, air purifiers, CO2 monitors and lots more.

Available from Amazon

To get the gist of HRV, it helps to know a few things about how your body functions. The following is a simplifed explanation.

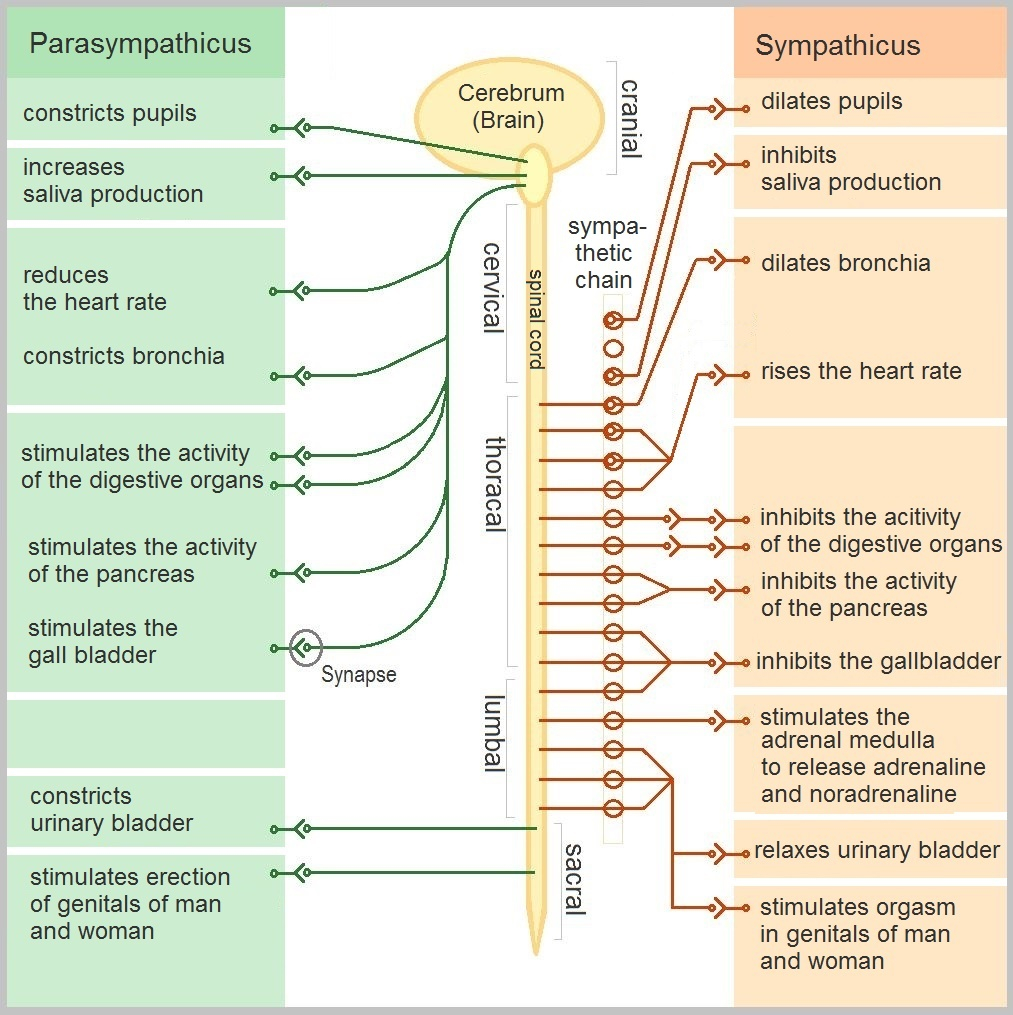

The Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system is the part of your body that regulates unconscious mechanisms like breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, digestion and the function of internal organs. These things help keep you alive and the ANS operates without you having to think about it. The ANS has two main modes or systems.

Sympathetic – the “fight or flight” mode. This response exists to protect us from threats and can be seen as a stress response. It speeds up the heart, dilates the pupils, slows digestion and can put bodily functions “on hold” until the threat is over.

Parasympathetic – the “rest and digest” mode. This bodily response kicks in when you are resting or not stressed. It slows the heart rate, encourages food to be digested and enables repair and recovery from illness.

When the body is functioning well, these two modes operate in balance with each other. Illness and stress can cause the pendulum to swing too far in one direction, either sympathetic or parasympathetic, and dysautonomia is the medical term for when the ANS does not function properly. Orthostatic intolerance or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) are two examples of dysautonomia. These problems appear to be a common aspect of Long Covid.

What Is Heart Rate Variability?

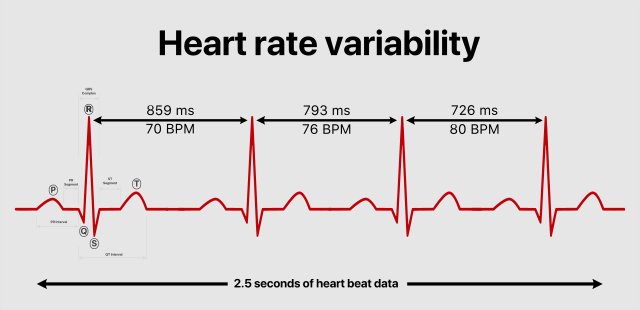

You’re probably aware that the heart beats a certain number of times per minute. The average healthy person’s heart rate is around 60 to 100 beats per minute, though this figure can of course be higher or lower depending on the person’s fitness or age. But that 60 beats a minute doesn’t happen like a metronome; the heart doesn’t beat exactly at the same time every time. There can be tiny differences between one heart beat and the next. So one beat may take 0.89 of a second, the next may take 1.15 of a second to complete. The measurement of those differences is what makes up heart rate variability (HRV) scores.

When the sympathetic nervous system is in charge, a person’s heart will beat in a more regular, clock-like fashion. There’s less variability in the beats. This is because the body is in fight-or-flight mode. When things switch to the parasympathetic mode, heart rate variability increases. The body is resting, relaxed, and the heart doesn’t have to be “standing to attention”, ready to run. Your body is more adaptable. This is a very non-scientific way to describe HRV, but it gives a general, simple idea of the whole thing.

HRV measurements are thus used to give an idea of the state of your autonomic nervous system, whether you are in a sympathetic or parasympathetic mode (or balanced) and thus, whether the body is under stress or is needing rest. If your HRV score is higher, you’re parasympathetic and in a more restful state. If it’s lower, you’re sympathetic and experiencing stress.

How is HRV Measured?

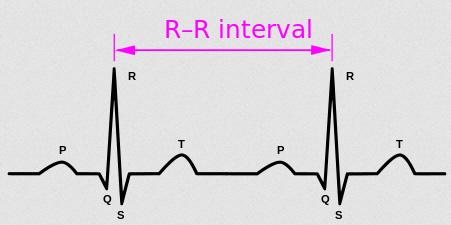

Measuring HRV is a fairly complicated mathematical process. On an electrocardiogram (ECG), HRV is called the R-R interval, where “R” is each spike of the heartbeat (”NN” can also be used). HRV measurements of this interval include the frequency of the beat (low or high), the power of each beat and the actual time between beats. There’s two main ways to measure – “time domain” and “frequency domain”. The former is more common. Various mathematical equations are used to calculate overall HRV and it can get pretty confusing. For the purposes of this guide, it’s easiest to talk about a single measurement that most trackers use: RMSSD.

RMSSD is an acronym that stands for “root mean square of the successive differences”. Yes, that’s very… maths-y. The important thing to remember is that this measurement has become something of a “gold standard” when measuring HRV and has a lot of scientific research backing it up as a handy number to use. Most HRV trackers will give an RMSSD figure and this means it’s the best measure to use in your own health tracking.

HRV can vary throughout the day and night. Things like eating, resting, stress and exercise make a difference to HRV readings. When it comes to taking a single HRV reading to try and get an idea of overall health, consistency is important. For a single reading, the best time is first thing in the morning, before getting out of bed. Preferably at the same time every day.

Thankfully, some wearables are able to offer HRV readings over a longer period of time. The Fitbit wearables track HRV overnight and give a single RMSSD score in the morning. The Garmin wearables that offer Body Battery are able to track HRV throughout the day. They don’t offer RMSSD numbers; instead, they convert HRV and heart rate data into a “stress score” and present it as a day-long graph, where blue equals times of less stress and orange means more stress. See the Wearables and Trackers page for more info.

What’s Normal HRV?

Everyone is different and so there’s no standard number that represents “normal” HRV. Most HRV tracking apps and wearables require multiple readings over several weeks to get an idea of what is “normal” for you. Even then, it helps to maintain measurements over a longer period of time to get an idea of your own rhythms and regular fluctuations. Correlating HRV measurements with other lifestyle factors like exercise, sleep and stress can then give you an idea of what causes your HRV to rise or fall. Alcohol can cause HRV to drop significantly, as can lack of sleep or extreme stress.

Most HRV apps aim to find your “baseline” HRV. This is the number where you’re ANS is balanced between sympathetic and parasympathetic. It might be called your own personal “normal”. Once a baseline is established, the app can tell you if you’re in a sympathetic or parasympathetic swing. The former means you’re stressed and need to take time to relax. The latter means you may be getting ill or are recovering from stress.

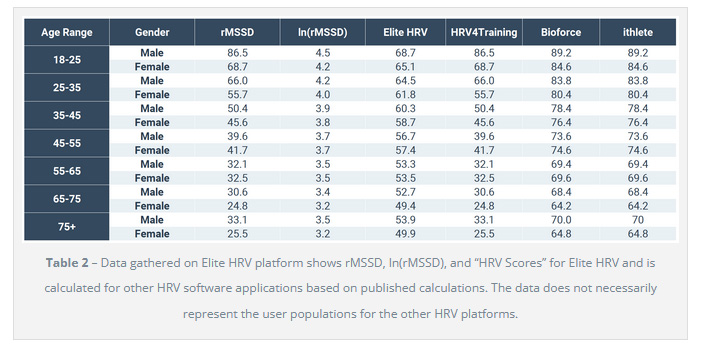

Elite HRV have published this page where they offer the average HRV scores and RMSSD figures for over ten thousand users, divided by sex and age. It’s clear that HRV scores tend to go down with age. Men’s scores tend to be higher than women’s. To give an example, a female aged 18-25 might have an RMSSD result of 68.7 milliseconds while a female aged 45-55 might have an RMSSD of 41.7 milliseconds. A male aged 25-35 might have an RMSSD of 66ms. A male aged 55-65 might have an RMSSD of 32.1ms.

HRV and Long Covid

HRV is worth tracking if you’re a Long Covid patient because it can give an overall picture of your health, showing improvements or declines over time. Measurements can give an idea of how much stress your body is experiencing and if you are vulnerable to excess stress. Given that some Long Covid patients have issues with orthostatic intolerance and other dysautonomic symptoms, HRV can offer insights into the extent of this dysfunction.

Ways to Improve HRV

It’s not a rule but typically people with chronic illnesses have lower HRV scores. If the body is in a constant state of stress or inflammation, heart rate variability goes down. Various scientific studies have shown that you can improve overall HRV with deep breathing, meditation, good sleep, eating well, drinking enough water, looking after your mental and emotional health and – if possible – exercise. You can read more about ways to improve your HRV on the Ways To Calm The Nervous System and Improve HRV page.

Stimulating the vagus nerve with non-invasive techniques is another possible way to improve HRV. This involves things like humming, immersion in cold water, certain yoga exercises and laughing. Not a lot of research has been done as to whether doing these things actually improves HRV or just makes you feel good. You can read more about this on the the Ways To Calm The Nervous System and Improve HRV page.

It’s been suggested that you can improve HRV by stimulating the the vagus nerve with transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS). This involves using a TENS device to pass electrical current through the ear. There is preliminary research suggesting that tVNS for Long Covid may be helpful but this treatment is still very experimental. You’ll find more info on the tVNS For Long Covid page plus a listing of tVNS devices with info on how to use them.

HRV Apps

There are a growing number of apps that help you to track your HRV. You’ll find them listed on the Best Apps For Long Covid page.

You’ll also find some apps that offer HRV biofeedback on the Deep Breathing Exercises for Long Covid page.

Research

Benarroch EE. Physiology and Pathophysiology of the Autonomic Nervous System. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2020 Feb;26(1):12-24. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000817. PMID: 31996619.

Barizien N, Le Guen M, Russel S, Touche P, Huang F, Vallée A. Clinical characterization of dysautonomia in long COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021 Jul 7;11(1):14042. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93546-5. PMID: 34234251; PMCID: PMC8263555.

Marques KC, Silva CC, Trindade SDS, Santos MCS, Rocha RSB, Vasconcelos PFDC, Quaresma JAS, Falcão LFM. Reduction of Cardiac Autonomic Modulation and Increased Sympathetic Activity by Heart Rate Variability in Patients With Long COVID. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Apr 29;9:862001. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.862001. PMID: 35571200; PMCID: PMC9098798.

Acanfora D, Nolano M, Acanfora C, Colella C, Provitera V, Caporaso G, Rodolico GR, Bortone AS, Galasso G, Casucci G. Impaired Vagal Activity in Long-COVID-19 Patients. Viruses. 2022 May 13;14(5):1035. doi: 10.3390/v14051035. PMID: 35632776; PMCID: PMC9147759.

Hayano J, Yuda E. Pitfalls of assessment of autonomic function by heart rate variability. J Physiol Anthropol. 2019 Mar 13;38(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s40101-019-0193-2. PMID: 30867063; PMCID: PMC6416928.

Fournié C, Chouchou F, Dalleau G, Caderby T, Cabrera Q, Verkindt C. Heart rate variability biofeedback in chronic disease management: A systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2021 Aug;60:102750. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2021.102750. Epub 2021 Jun 10. PMID: 34118390.

Reneau M. Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback to Treat Fibromyalgia: An Integrative Literature Review. Pain Manag Nurs. 2020 Jun;21(3):225-232. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2019.08.001. Epub 2019 Sep 26. PMID: 31501080.

Lampros M, Vlachos N, Zigouris A, Voulgaris S, Alexiou GA. Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation (t-VNS) and epilepsy: A systematic review of the literature. Seizure. 2021 Oct;91:40-48. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2021.05.017. Epub 2021 May 24. PMID: 34090145.

Yuan H, Silberstein SD. Vagus Nerve and Vagus Nerve Stimulation, a Comprehensive Review: Part II. Headache. 2016 Feb;56(2):259-66. doi: 10.1111/head.12650. Epub 2015 Sep 18. PMID: 26381725.

Farmer AD, Albu-Soda A, Aziz Q. Vagus nerve stimulation in clinical practice. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2016 Nov 2;77(11):645-651. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2016.77.11.645. PMID: 27828752.

Links

What is Heart Rate Variability? The definitive guide to HRV – Sophie Lezama, Elite HRV, March 2022